- Saturday, 29 January - On Peter I

- At 2:00 PM we rushed to the bridge. Peter I Island, almost indistinguishable from an iceberg, was low on the horizon, drifting in and out of the clouds. As we watched transfixed, it loomed larger and larger, dwarfing the bergs. The sun burned brightly on part of the island, while clouds and mist hid the rest. We were impressed with how much it looked like the pictures we had seen. In spite of having never seen it before, we had a feeling of familiarity.

-

- As we approached the island, we got good views of the edge of the glacier. It tumbled over the rocks and into the sea, white frosting on dark chocolate. Very, very, very gently we set the helo down; we had landed!

-

- This moment was an emotional high&emdash;we laughed and congratulated ourselves and shook hands and opened a bottle of champagne. As the whine of the helicopter faded and the ship became an insignificant speck on the ocean, we were suddenly confronted with the awesomeness of our isolation. For better or worse, this was going to be home for three weeks. The sounds of engines was replaced by the sounds of boots squishing in the snow, and hammers, and men's voices damped out by snow and ice. Everywhere around us was just snow and ice.

-

- Monday, 31 January

- Late in the afternoon we were treated to a spectacular light show. As the sun approached the edge of the mountain behind our camp, the wispy clouds circling the peaks were set ablaze into a fiery display of pink, contrasting against the deep blue of the sky. It lasted more than an hour. As the sun slipped behind the western edge of the mountain, the moon rose from its eastern edge. Now and then we saw two or three large white birds, Antarctic fulmars, sail overhead at high speed, riding the west winds. Martin saw a large iceberg suddenly break completely in two.

-

- Tuesday, 1 February

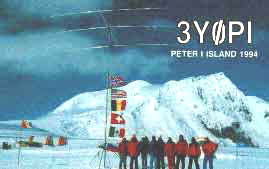

- At 3 o'clock in the afternoon&emdash;2100 UTC&emdash;the stations were ready. Ralph entered the SSB tent, and tuned up on 14.195 MHz. 3YØPI came up on schedule. Peter I Island was on the air!

-

- With four stations operating, four people suddenly disappeared from camp, and others disappeared into their sleeping bags to catch up, or stock up, on sleep. The place seemed deserted. Previously we had jammed into the cook tent for Martin's gourmet rehydrated dehydrated meat granules and processed canned cheese and chocolate bars for dessert; now one or two people would appear, eagerly greeting anyone else who might stop in.

-

- Thursday, 3 February

- The wind continued to build. The snow was blowing over the crates and forming dunes in front of the shelters. The landscape began to change&emdash;as the snow built into drifts, the camp began to have a different geometry. Our paths between the tents, latrine, generators, and gas barrels began to change; we started losing sight of some of the gear, and realized that we had to dig if we were going to keep track of it. Periodically the mountain disappeared entirely, either behind the clouds or deep in the unfocused depths of the fog. The snow piled so high and fast it shut down the generators. The radios went dead, and everyone went to bed. Lying there, we had just two thoughts: "We're missing Q's," and "Please, Dear God, keep this tent together!"

-

- Tuesday, 8 February

- The cliffs rose in indescribable massiveness almost a mile above us. The rocks were so steep the ice couldn't get a grip on much of it. As we walked along the steep slope, small rocks and pebbles were rolling down around us. Finally, we reached the bare rock outcrop that we had seen in the photographs, and for the first time we could claim we had touched Peter I.

-

- Sunday, 20 February

- The Akademik Fedorov arrived on Feb. 16. Our elation at their arrival was decimated by a sudden condensation of dense fog&emdash;there would be no helicoptering this day. After partial dismantling of the camp in preparation for the airlift, we found ourselves with nothing much to do but continually dig gear out of the blowing snow.

-

- After four days we began to have remote hopes of getting off. We worked furiously, digging, digging, hauling, hauling. Finally, we were looking for things to carry. Turning around, I was unprepared for what I saw: there was nothing but snow, blowing gently into the temporary depressions left from our shelters and footprints. The sharp corners were already being rounded; a patina of pure white was masking the marks of boots and boxes. The visual lock we had had for weeks was quickly ebbing into a featureless flow.

-

- Then the significance of what we had just done came in like a meteor: we had taken everything, everything that we came with, back with us. We left not one bag, barrel, board, box, can, or crate. We didn't leave spilled chemicals or bits of string or styrofoam. We didn't even leave our human waste. We left nothing. Nothing! I had a sudden rush of euphoria: We had done it! We had done it!

-

- Turning away was not easy. The island was magnificent, a towering monument to a great man that could just as well have been a holy place, the dwelling place of the Almighty. Towering among and above the clouds, mantled in mist and protected by a guard of icy monoliths, it could easily have been a sacred place, revered but never violated. No person had as yet scaled the mountain; much of it was as yet unseen. Mysterious, incomprehensible, enigmatic. If only it hadn't been so far from anywhere, and so isolated. The Most-Isolated-Place-On-Earth.

-

- Sunday, 27 February

- As we settled into the long flight to Miami, fatigue and nostalgia caught up. It was hard to fathom it all: that we had been away from home for a month and a half, that we had completed what might be the logistically most complicated DXpedition ever, that it had gone on schedule and on budget, that no one was hurt and nothing of great value was lost, that we had made hundreds of friends along the way and had 60,000 contacts in the logs.

-

- Privately each of us slipped into a review of what had happened, of what it meant to us and to thousands of others who shared the experience in big and little ways, of how we would react to becoming ordinary people again. We thought about the beauty of Peter I Island and of its slim history of exploration, of our good luck in getting on and not-so-bad luck in getting off. We thought about the fragments of radio waves that even now are speeding outward from Earth into the cosmos, carrying our words in our voices and those of thousands of others: 3YØPI. Five-and-nine. Thanks. 73. QRZ?. We thought about the miracle of wireless communication, the miracle of flight, the miracle of life.

-

- Mostly, though, we thought about Where Would We Go Next?

|